Evanescent wave

An evanescent wave is a near-field standing wave with an intensity that exhibits exponential decay with distance from the boundary at which the wave was formed. Evanescent waves are a general property of wave-equations, and can in principle occur in any context to which a wave-equation applies. They are formed at the boundary between two media with different wave motion properties, and are most intense within one third of a wavelength from the surface of formation. In particular, evanescent waves can occur in the contexts of optics and other forms of electromagnetic radiation, acoustics, quantum mechanics, and "waves on strings".[1][2]

Contents |

Evanescent wave applications

In optics and acoustics, evanescent waves are formed when waves traveling in a medium undergo total internal reflection at its boundary because they strike it at an angle greater than the so-called critical angle.[1][2] The physical explanation for the existence of the evanescent wave is that the electric and magnetic fields (or pressure gradients, in the case of acoustical waves) cannot be discontinuous at a boundary, as would be the case if there was no evanescent wave field. In quantum mechanics, the physical explanation is exactly analogous—the Schrödinger wave-function representing particle motion normal to the boundary cannot be discontinuous at the boundary.

Electromagnetic evanescent waves have been used to exert optical radiation pressure on small particles in order to trap them for experimentation, or to cool them to very low temperatures, and to illuminate very small objects such as biological cells for microscopy (as in the total internal reflection fluorescence microscope). The evanescent wave from an optical fiber can be used in a gas sensor, and evanescent waves figure in the infrared spectroscopy technique known as attenuated total reflectance.

In electrical engineering, evanescent waves are found in the near-field region within one third of a wavelength of any radio antenna. During normal operation, an antenna emits electromagnetic fields into the surrounding nearfield region, and a portion of the field energy is reabsorbed, while the remainder is radiated as EM waves.

In quantum mechanics, the evanescent-wave solutions of the Schrödinger equation give rise to the phenomenon of wave-mechanical tunneling.

In microscopy, systems that capture the information contained in evanescent waves can be used to create super-resolution images. Matter radiates both propagating and evanescent electromagnetic waves. Conventional optical systems capture only the information in the propagating waves and hence are subject to the diffraction limit. Systems that capture the information contained in evanescent waves, such as the superlens and near field scanning optical microscopy, can overcome the diffraction limit; however these systems are then limited by the system's ability to accurately capture the evanescent waves.[3] The limitation on their resolution is given by

,

,

where  is the maximum wave vector that can be resolved,

is the maximum wave vector that can be resolved,  is the distance between the object and the sensor, and

is the distance between the object and the sensor, and  is a measure of the quality of the sensor.

is a measure of the quality of the sensor.

More generally, practical applications of evanescent waves can be classified in the following way:

- Those in which the energy associated with the wave is used to excite some other phenomenon within the region of space where the original traveling wave becomes evanescent (for example, as in the total internal reflection fluorescence microscope)

- Those in which the evanescent wave couples two media in which traveling waves are allowed, and hence permits the transfer of energy or a particle between the media (depending on the wave equation in use), even though no traveling-wave solutions are allowed in the region of space between the two media. An example of this is so-called wave-mechanical tunnelling, and is known generally as evanescent wave coupling.

Total internal reflection of light

For example, consider total internal reflection in two dimensions, with the interface between the media lying on the x axis, the normal along y, and the polarization along z. One might naively expect that for angles leading to total internal reflection, the solution would consist of an incident wave and a reflected wave, with no transmitted wave at all, but there is no such solution that obeys Maxwell's equations. Maxwell's equations in a dielectric medium impose a boundary condition of continuity for the components of the fields E||, H||, Dy, and By. For the polarization considered in this example, the conditions on E|| and By are satisfied if the reflected wave has the same amplitude as the incident one, because these components of the incident and reflected waves superimpose destructively. Their Hx components, however, superimpose constructively, so there can be no solution without a non-vanishing transmitted wave. The transmitted wave cannot, however, be a sinusoidal wave, since it would then transport energy away from the boundary, but since the incident and reflected waves have equal energy, this would violate conservation of energy. We therefore conclude that the transmitted wave must be a non-vanishing solution to Maxwell's equations that is not a traveling wave, and the only such solutions in a dielectric are those that decay exponentially: evanescent waves.

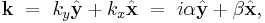

Mathematically, evanescent waves can be characterized by a wave vector where one or more of the vector's components has an imaginary value. Because the vector has imaginary components, it may have a magnitude that is less than its real components. If the angle of incidence exceeds the critical angle, then the wave vector of the transmitted wave has the form

which represents an evanescent wave because the y component is imaginary. (Here α and β are real and i represents the imaginary unit.)

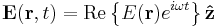

For example, if the polarization is perpendicular to the plane of incidence, then the electric field of any of the waves (incident, reflected, or transmitted) can be expressed as

where  is the unit vector in the z direction.

is the unit vector in the z direction.

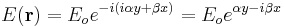

Substituting the evanescent form of the wave vector k (as given above), we find for the transmitted wave:

where α is the attenuation constant and β is the propagation constant.

Evanescent-wave coupling

In optics, evanescent-wave coupling is a process by which electromagnetic waves are transmitted from one medium to another by means of the evanescent, exponentially decaying electromagnetic field.

Coupling is usually accomplished by placing two or more electromagnetic elements such as optical waveguides close together so that the evanescent field generated by one element does not decay much before it reaches the other element. With waveguides, if the receiving waveguide can support modes of the appropriate frequency, the evanescent field gives rise to propagating-wave modes, thereby connecting (or coupling) the wave from one waveguide to the next.

Evanescent-wave coupling is fundamentally identical to near field interaction in electromagnetic field theory. Depending on the impedance of the radiating source element, the evanescent wave is either predominantly electric (capacitive) or magnetic (inductive), unlike in the far field where these components of the wave eventually reach the ratio of the impedance of free space and the wave propagates radiatively. The evanescent wave coupling takes place in the non-radiative field near each medium and as such is always associated with matter; i.e., with the induced currents and charges within a partially reflecting surface. This coupling is directly analogous to the coupling between the primary and secondary coils of a transformer, or between the two plates of a capacitor. Mathematically, the process is the same as that of quantum tunneling, except with electromagnetic waves instead of quantum-mechanical wavefunctions.

Applications

- Evanescent wave coupling is commonly used in photonic and nanophotonic devices as waveguide sensors.

- Evanescent wave coupling is used to excite, for example, dielectric microsphere resonators.

- A typical application is resonant energy transfer, useful, for instance, for charging electronic gadgets without wires. A particular implementation of this is WiTricity; the same idea is also used in some Tesla coils.

- Evanescent coupling, as near field interaction, is one of the concerns in electromagnetic compatibility.

- Evanescent wave coupling plays a major role in the theoretical explanation of extraordinary optical transmission.[4]

See also

- Coupling (electronics)

- Electromagnetic wave

- Quantum tunneling

- Resonant energy transfer

- Snell's law

- Total internal reflection

- Total internal reflection fluorescence microscope

- Waveguide

References

- Karalis, Aristeidis; J.D. Joannopoulos, Marin Soljačić (February 2007). "Efficient wireless non-radiative mid-range energy transfer". Annals of Physics 323: 34. arXiv:physics/0611063v2. Bibcode 2008AnPhy.323...34K. doi:10.1016/j.aop.2007.04.017.

- "'Evanescent coupling' could power gadgets wirelessly", Celeste Biever, NewScientist.com, 15 November 2006

- Wireless energy could power consumer, industrial electronics - MIT press release

- ^ a b Tineke Thio (2006). "A Bright Future for Subwavelength Light Sources". American Scientist (American Scientist) 94 (1): 40–47. doi:10.1511/2006.1.40.

- ^ a b Marston, Philip L.; Matula, T.J. (May 2002). "Scattering of acoustic evanescent waves...". Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 111 (5): 2378. Bibcode 2002ASAJ..111.2378M.

- ^ Neice, A., "Methods and Limitations of Subwavelength Imaging", Advances in Imaging and Electron Physics, Vol. 163, July 2010

- ^ Z. Y. Fan, L. Zhan, X. Hu, and Y. X. Xia, "Critical process of extraordinary optical transmission through periodic subwavelength hole array: Hole-assisted evanescent-field coupling," Optics Communications 281, 5467-5471 (2008).